Bricolage

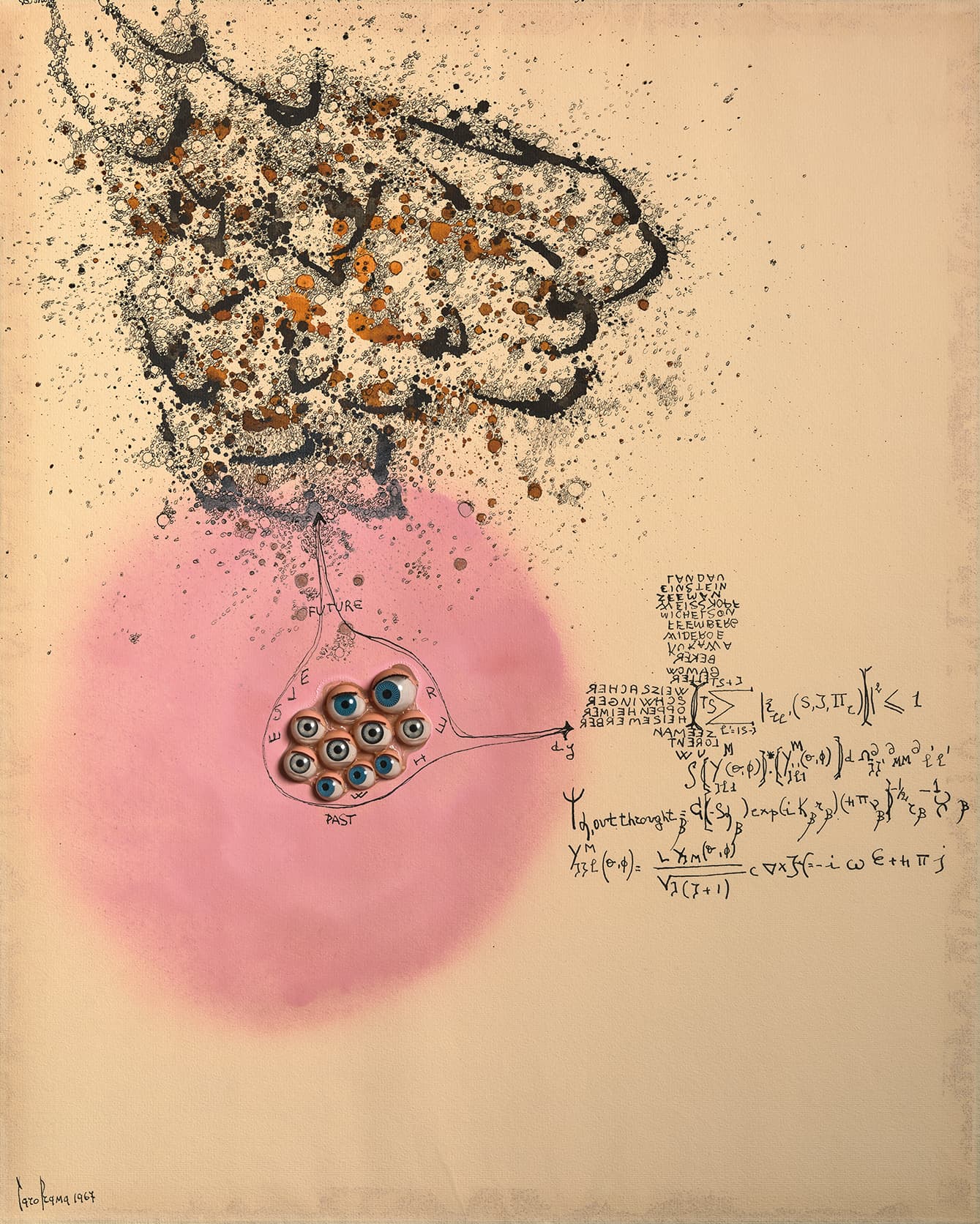

At the beginning of the 1960s, Carol Rama opened up the flat surface of the canvas, expanding it by using objects from her everyday life. Such an approach to materials was in the air during the 1960s. In a period of social and political awakening that entailed critiques of consumerism and protests against traditional Western art history, attempts were being made to bring art and everyday life together. This radical attitude was to be likewise found among artists involved in Arte Povera, the latter subsequently emerging in Turin. Rama painted with glue, enamel, oil and spray paint, utilising metal shavings, paint tubes, dolls’ eyes and much more, returning to motifs from her early watercolours in an echo of the prosthesis imagery. In 1964, the poet Edoardo Sanguineti, a close friend of Rama’s, dubbed her experiments with materials “Bricolage”. He was referencing the French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, who had used the term to describe a form of thinking that draws on what is available in finding solutions to problems, therefore requiring both openness and improvisation. The term subsequently became established in Western art history.

The series Autorattristatrice from 1968–1969 belongs to the Bricolage group of works. The so-called “napalm paintings” were created as a reaction to the Vietnam War, enabling Rama to explicitly condemn the use of weapons of mass destruction. She said of the series: “These paintings were like burned and tortured people, always involving problems of the body and Eros, made with bad materials like black spray paint and glued-on eyes. I always had the need to create mutilation. Perhaps it was also a mutilation that the war had inflicted on me.” Tellingly, the title is a combination of rattristatrice – a woman causing sadness – and the prefix auto, suggesting that the woman is making herself sad. The play on words also conjures the term autoritratto (self-portrait).