Introduction

Swiss art forms a major part of Kunstmuseum Bern’s collection. The current display focuses on certain aspects that are characteristic of the works of art being produced in Switzerland during the 19th and early 20th centuries, while simultaneously presenting important groups of works from the painting collection.

The display begins with Symbolist works in which artists were seeking to convey, beyond realistic representation, deeper, hidden desires, truths and feelings. The presentation starts in the stairwell with the section Dialogue with Nature, addressing humanity’s desire for a spiritual connection with nature. In the first gallery a dark counterpoint follows with Hidden Reality in the form of allegorical, mythological and melancholic painterly inventions. The next section,The Transience of Being, presents works ranging from Albert Anker to Annie Stebler-Hopf that approach the subject of mortality and death from the perspective of Realist painting.

The section Ode to the Alps is dedicated to the tradition of depicting the Swiss mountain landscape, while Serene Strength, in the following gallery, brings together works portraying the rural population going about their work. Expressive Worlds in the ancillary gallery assembles works by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and the Swiss Expressionists involved in the Rot-Blau (Red Blue) group of artists. The exhibition concludes with Bourgeois Leisure, a presentation of works ranging from Cuno Amiet to Louis Moilliet, exploring the various aspects of urban leisure activities.

I. Dialogue with Nature

Swiss artists at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century evoked their vision of the spiritual connection between humanity and nature by depicting figures immersed in the landscape, poignant gestures, dance-like movements and enraptured faces. The figures are in a dialogue with nature, as a work title by Ferdinand Hodler (Zwiegespräch mit der Natur) puts it. Their bodies become vehicles of spiritual sensations and their nudity underscores their oneness with the cosmos.

The desire for such an idyll is characteristic of the turn of the century zeitgeist. Against a backdrop of industrialisation, urbanisation and the mechanisation of all areas of life, many felt and were critical of humanity’s increasing alienation from nature and therefore from themselves. Under the motto of Lebensreform (life reform), a variety of social reform movements in Germany and Switzerland began striving for a ‘natural way of living’ that would restore the harmony of body, mind and soul.

The fin-de-siècle mentality was likewise echoed in the work of artists, who responded to the modern world with a range of counter-concepts. One of them was of humankind existing in a quasi-paradisiacal state of blissful harmony with nature, as portrayed in works by artists ranging from Giovanni Giacometti to Victor Surbek.

II. Hidden Reality

In a reaction to the Rationalist view of the world prevailing at the end of the 19th century and the hegemony of the natural sciences, a way of thinking evolved that began questioning visible reality and the power of reason. In a search for deeper truths, there was a turn to the supernatural and the mysterious.

In art, this meant a departure from Realism and Naturalism, which were dedicated to faithful depictions of reality while eschewing any form of stylisation. Instead there was an increasing interest in the ‘other’: in the unconscious, the uncanny and the instinctual, in dreams and hypnosis, maladies of body and soul, spirituality and the esoteric as well as myths and legends. From their exploration of such subjects, artists began creating imagery that opposed reality as normally experienced, and whose diverse styles and forms of expression are compiled under the term ‘Symbolism’.

Many works possessed a symbolic character, employing allegorical figures, for example, in seeking a higher meaning beyond the content being depicted. Ernest Biéler personified autumn in such a manner in Les feuilles mortes (Dead Leaves), in the form of stylised female figures. Arnold Böcklin’s ominous-looking scenes populated by hybrid creatures can be read as allegories of war or the struggle between the sexes. Ferdinand Hodler, on the other hand, renounced such mythological references in favour of creating figures that, in the way they pose and the use of repetition, point beyond themselves, becoming timeless symbols of transience and death.

III. The Transience of Being

During the second half of the 19th century, numerous representatives of Realism likewise confronted the transience of being. Death was frequently portrayed as being part of everyday life, for example in Albert Anker’s Die kleine Freundin (The Little Friend) or Max Buri’s Nach dem Begräbnis (After the Funeral).

The religious genre continued to be popular, as demonstrated by Ferdinand Hodler’s depiction of believers immersed in prayer in his painting Gebet im Kanton Bern (Prayer in the Canton of Bern). In this early work, the artist employed lifelike depictions in a portrait-like manner to anchor the figures in the here and now. The portraitist Karl Stauffer-Bern treated the Gekreuzigter (Crucified Christ) in the same way, transforming Christ from a saviour into a lifelike contemporary figure.

Annie Stebler-Hopf’s painting Am Seziertisch (Professor Poirier, Paris) (At the Dissecting Table [Professor Poirier, Paris]) represents a novel motif. In depicting the subject matter in a very sobering scene, it expresses a then current interest in the anatomy of the human body as well as contemporary achievements in medicine and its methods.

IV. Ode to the Alps

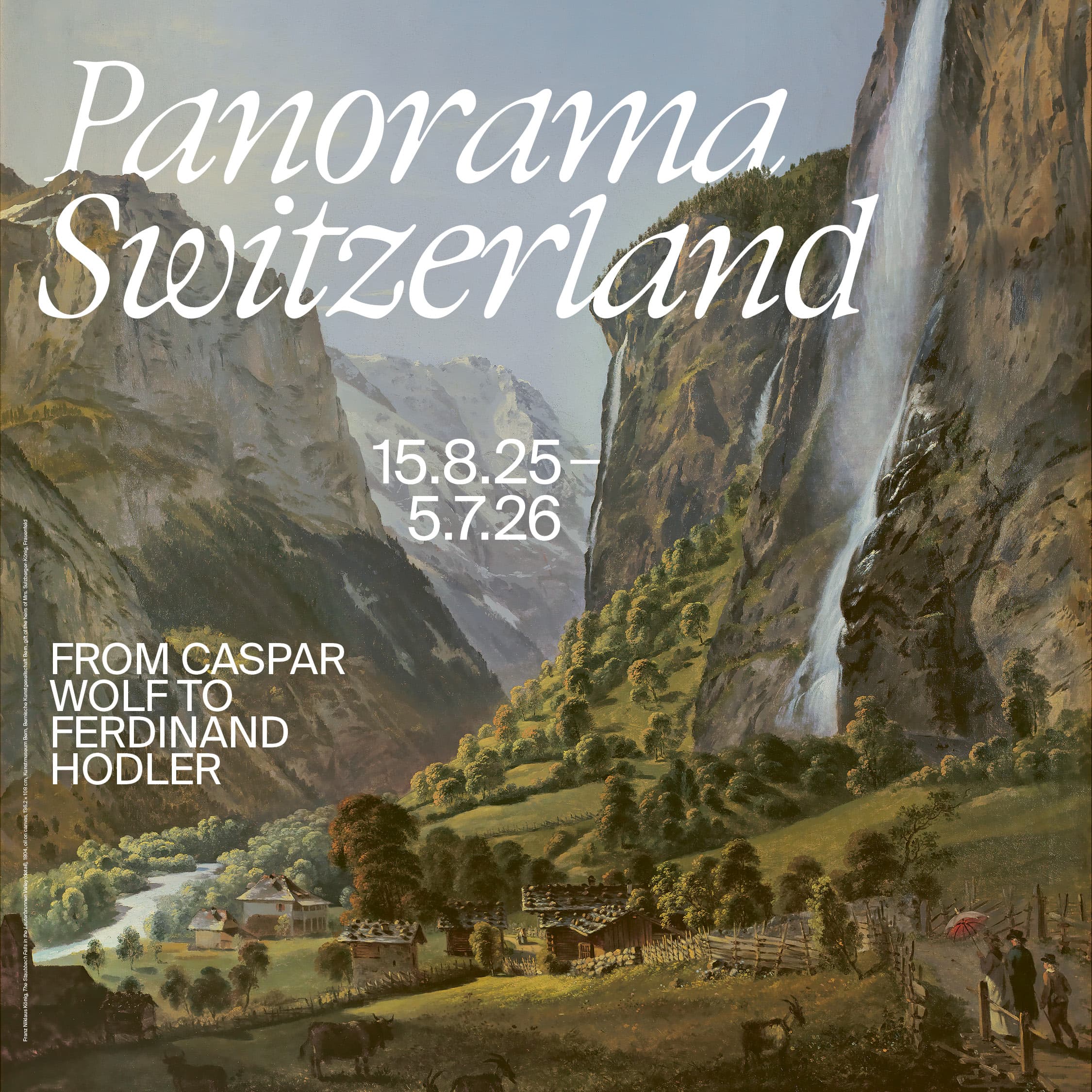

The Alpine landscape is an unmistakable feature of Switzerland and is therefore also one of Swiss art’s central subjects. It was not until the 18th century, during the Age of Enlightenment and Romanticism, that artists ventured into the inhospitable high mountains while accompanying naturalists, producing precise depictions of peaks, glaciers, and mountain lakes. Among them was Caspar Wolf, who today is regarded as one of the pioneers of Swiss landscape painting.

As a result of scientific exploration and the rise of tourism, the Alps gradually underwent a reinterpretation, being transformed from a fearsome obstacle into a haven of unspoilt nature, harmony and democracy. Such perceptions informed by national identity went on to fuel tourism. Depictions of the Alpine region and its people subsequently gained importance and increasingly developed into a specialised branch of printmaking and landscape painting, and which also served the demand for souvenirs. For example, in the paintings of Franz Niklaus König, the imagery focuses on generic scenes incorporating shepherds, mountain huts and hikers, stylising the Alpine region as an idyllic haven.

During the 19th century, artists such as Gottfried Steffan and Alexandre Calame favoured more romantically heroic motifs. They celebrated the majesty of the Alps in dramatic scenes involving atmospheric thunderstorms and the effects of light. Such imagery focused on the enormous forces of nature, while humans appeared, at most, as insignificant accessories. During the Modern era, Alpine painting underwent further development through approaches favouring formal simplification. Ferdinand Hodler, in particular, is considered an innovator of the genre.

V. Serene Strength

From the second half of the 19th century onwards, depictions of peasant and working-class milieus became increasingly prevalent in Swiss art. Unlike many of their French and German colleagues, most Swiss artists produced motifs that were less socially critical in denouncing the harsh living and working conditions of specific social classes, but rather depictions of the milieu in which they themselves had grown up or now lived. These take the form of contemplative scenes depicting farmers and craftsmen at work, resting and socialising.

The rural population embodied a lifestyle involving an immersion in nature, modest living and hard work, which became elevated to an important component of national identity. Such depictions and how they were received often entailed a patriotic tone, which only intensified with the rise of nationalism at the beginning of the 20th century.

An example would be Ferdinand Hodler’s composition Der Holzfäller (The Woodcutter), which he conceived, together with Der Mäher (The Mower), for a series of banknotes on the subject of ‘work in Switzerland’. Executed as a monumental figure, the artist described the Holzfäller as ‘an unparalleled image of passionate, yet purposeful and serene strength, one that is almost impossible to tire of’. The iconic image quickly enjoyed great popularity, was repeated by Hodler in several subsequent versions and remains one of his best-known works today.

VI. Expressive Worlds

The German Expressionist Ernst Ludwig Kirchner also became involved in the Swiss mountains and rural population as subjects after settling in Davos in 1917. His adopted home provided him with new artistic inspiration and motifs. He produced mountain landscapes that were expressive in both colour and form, describing himself as an innovator of Alpine painting, working in the wake of Ferdinand Hodler.

A number of young Basel-based artists were inspired by Kirchner’s work, which was presented in an exhibition at Kunsthalle Basel in 1923. Albert Müller, Hermann Scherer, Werner Neuhaus, Paul Camenisch and Otto Staiger sought to connect with Expressionism and founded the Rot-Blau (Red Blue) group of artists on New Year’s Eve 1924/1925. They visited Kirchner in Davos, where they received both inspiration and advice.

Instead of an objective reproduction of visible reality, the artists were striving for an immediate form of expression informed by subjective experiences and feelings. Inspired by the style of the Brücke group of artists, they developed a form of landscape and figure painting characterised by its raw formal language and intensely vibrant colours.

VII. Bourgeois Leisure

In addition to mountain scenery and the working population, Swiss artists at the beginning of the 20th century began to increasingly focus on the urban environment and, with it, the pleasures of the bourgeoisie. Public recreational spaces and leisure venues, as well as showpeople and their audiences, became important subjects in the art of western Modernism.

Parks offering a respite from the hustle and bustle of the city and simultaneously serving as a space for social gatherings became popular motifs. For example, Martha Stettler, who lived in Paris, depicted people strolling and children playing in atmospheric en plein air scenes such as Le Parc (The Park). At the same time, the depiction of private interiors, which served as a space for domestic leisure and a retreat from the increasingly noisy outside world, likewise gained in importance.

Other artists produced portraits of dancers or scenes from concert halls and variety shows, focussing on the differing aspects of cultural leisure activities. Louis Moilliet, for example, explored the world of the circus and its performers in several paintings, while Cuno Amiet dedicated two large-scale works from the 1920s to musicians.

Imprint

Panorama Switzerland. From Caspar Wolf to Ferdinand Hodler

Kunstmuseum Bern

15.8.2025–5.7.2026

Curator: Anne-Christine Strobel

Scientific Trainee: Michelle Sacher

Exhibition Design: Jeannine Moser

Audio Guide

Text: Kunstmuseum Bern

Implementation: tonwelt GmbH

Digital Guide

Implementation: NETNODE AG

Project: Andriu Deflorin, Cédric Zubler

With the support of:

Kunstmuseum Bern

Hodlerstrasse 8–12, 3011 Bern

+41 31 328 09 44

info@kunstmuseumbern.ch

kunstmuseumbern.ch/panorama-switzerland